Until recently, the word “exoplanet” seemed more suited to speculation than astronomy. Isaac Newton had already suggested in the “Scholium Generale” of Principia Mathematica that fixed stars could be the centre of systems similar to ours, but science took centuries to prove it. It was only in the late 1980s that the first signs of planets outside the Solar System began to appear, although it was not until 1992 that the existence of worlds beyond the Sun was confirmed for the first time, around the pulsar PSR B1257+12.

In recent decades, the pace of discoveries has skyrocketed thanks to increasingly accurate instruments that have allowed us to locate worlds as strange as they are fascinating. The Kepler space telescope, for example, identified Kepler-16b more than a decade ago, a planet with ‘two suns’ reminiscent of Tatooine from Star Wars. Since then, we have catalogued a huge variety of exoplanets, but now the James Webb telescope presents a particularly impressive discovery: a world of boiling lava that, to the surprise of astronomers, is cooler than theoretical models predict.

An extreme world that questions what we know

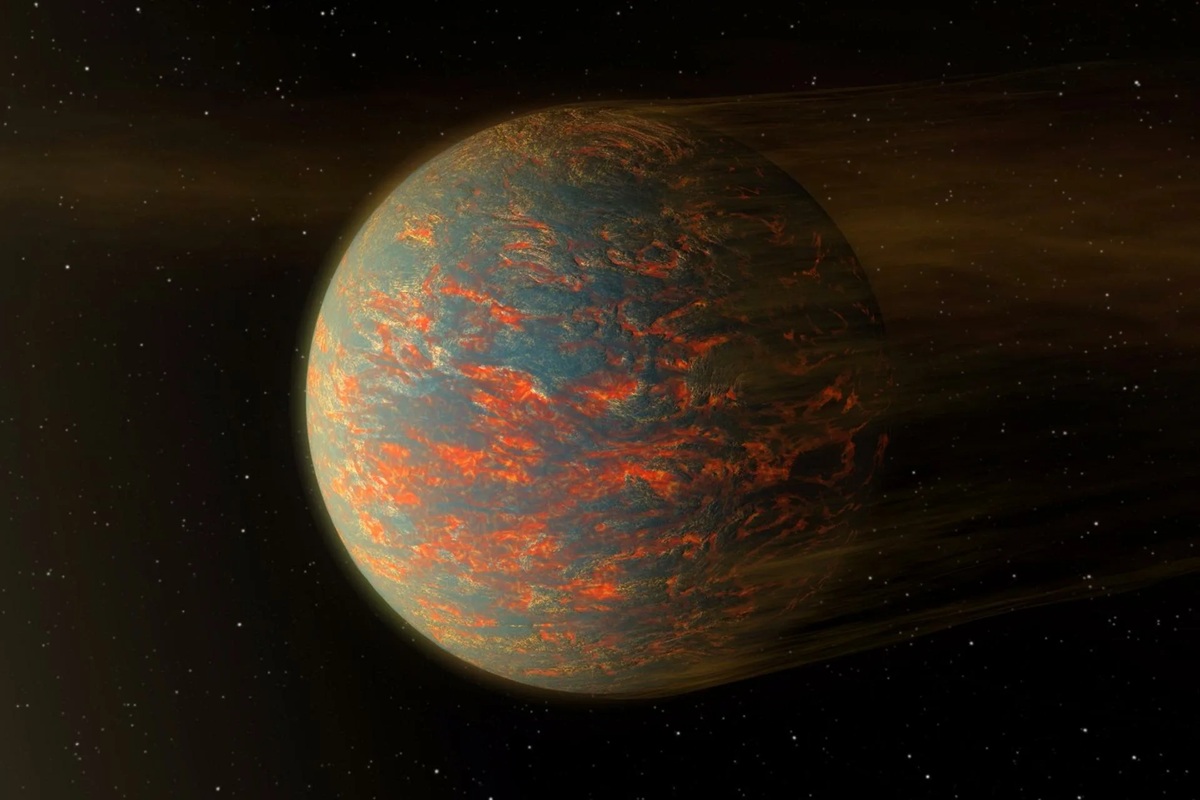

With a radius approximately 1.4 times that of Earth, TOI-561 b is an extreme super-Earth orbiting a star located about 280 light-years away in the constellation Sextans. NASA describes it as the innermost planet in a system composed of four worlds, with one immediate peculiarity: it completes an orbit in less than eleven hours. Its proximity is so extreme, only 0.01 astronomical units, that the daytime hemisphere must far exceed the melting point of rocks. Everything points to a planet trapped by its star in a tidal lock, with an eternal day on one side and a perpetual night on the other.

One of the peculiarities that most confuses researchers is the low density of TOI-561 b. Astronomer Johanna Teske, lead author of the study, explains that ‘it’s not a super-puff, but it’s less dense than you’d expect with a composition similar to Earth’s.’ The team considered that the planet had a small iron core and a mantle formed by less compact minerals, a possibility that would fit in with the chemistry of its star. As it is a very old G-type star, about 10 billion years old and poor in iron, located in the thick disc of the Milky Way, it is plausible that the planet arose in a primordial environment different from the Solar System.

Even so, the exotic composition did not solve all the unknowns, and the team began to consider another possibility: that TOI-561 b was enveloped by a thick atmosphere. The idea is intriguing because models indicate that small planets subjected to such intense radiation for billions of years should have lost their gases long ago. NASA points out, however, that some worlds of this type show signs that they are not simply bare rocks. This nuance opened the door to thinking that the low density could be due, in part, to a volume inflated by a substantial layer of gases.

To test the idea of a dense atmosphere, the team used a technique that James Webb has used on other rocky worlds: measuring the disappearance of part of the infrared brightness when the planet passes behind its star. Using the NIRSpec spectrograph, the researchers estimated the temperature of the illuminated hemisphere and compared it with what would be expected for a surface without gases to distribute heat. If TOI-561 b were a bare rock, its temperature would be around 2700 °C. However, observations placed this value at around 1,800 °C, a difference too large to be ignored.

The unexpectedly low temperature makes sense if TOI-561 b is surrounded by a dense atmosphere full of volatiles. In that case, winds would carry heat from the illuminated hemisphere to cooler areas, reducing the infrared emission received by the telescope. Gases capable of absorbing some of the radiation before it escapes into space also come into play, which coincides with the models evaluated by the team. It is even possible that there are clouds of silicates that reflect the star’s light and contribute to cooling the upper layers of the atmosphere.

To explain how TOI-561 b maintains such a resistant atmosphere, the researchers propose a mechanism in which magma and gases are in constant exchange. Tim Lichtenberg notes that as the interior releases volatile compounds into the atmosphere, the ocean of molten rock recaptures some of them, reducing the loss to space. This process requires a planet exceptionally rich in volatile substances, very different from Earth in its initial composition. In Lichtenberg’s words, it would be ‘like a wet lava ball,’ a description that sums up the extreme nature of the discovery.

The observations that made it possible to reconstruct this scenario are part of the James Webb’s General Observers 3860 programme. For more than 37 hours, the telescope continuously tracked the system as TOI-561 b completed nearly four full orbits, a record that offers an exceptional view of how its brightness varies along the way. With this volume of data, the team is now analysing how the temperature changes around the planet and what clues this provides about the composition of its atmosphere. This data set, still under analysis, points to a more complex world than was imagined in the first observations.

The case of TOI-561 b demonstrates that even the most extreme worlds can hold surprises. Far from being a simple scorched rock, Webb’s observations describe a dynamic system in which magma, atmosphere and stellar radiation interact in ways we do not yet fully understand. As Johanna Teske notes, ‘What’s really exciting is that this new set of data is raising even more questions than answers.’ The investigation continues, and each new analysis seems to confirm that this planet belongs to a category we are only beginning to understand.