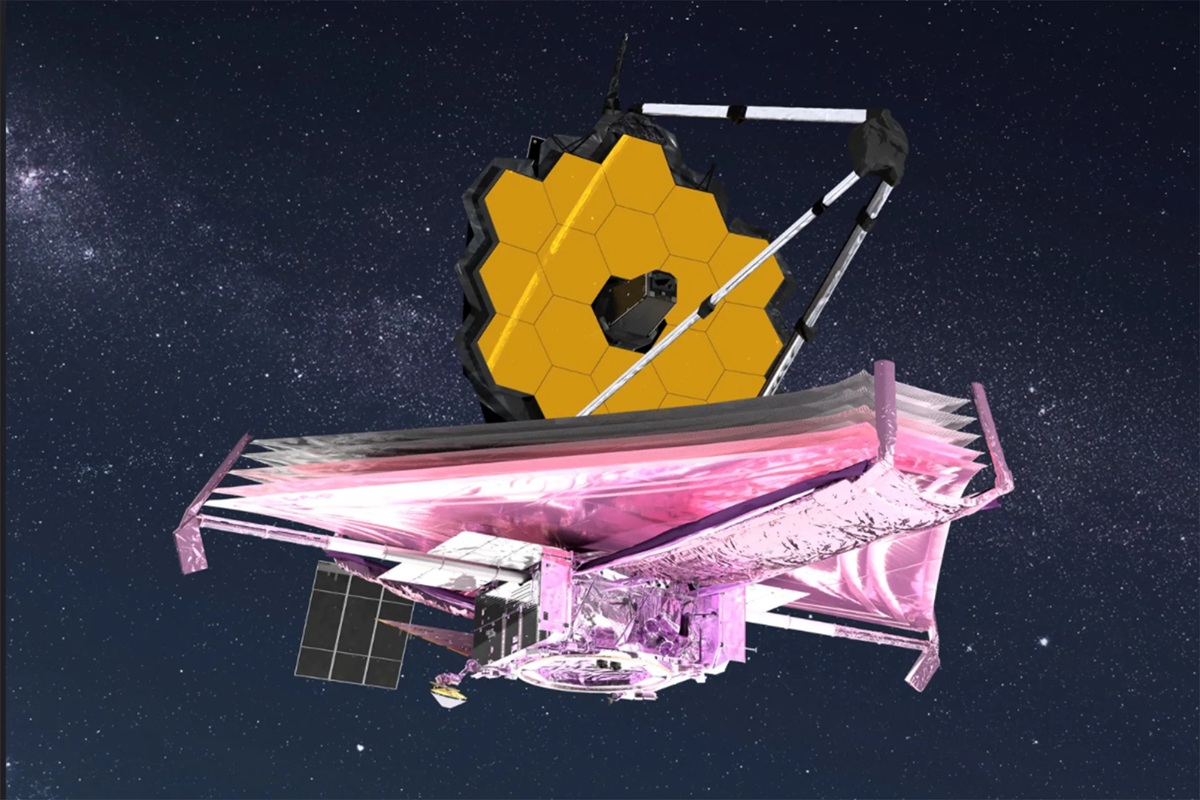

The planet TOI-561 b, an ultra-hot super-Earth located outside our solar system, is surrounded by a thick layer of gases covering a global ocean of magma. It is the strongest evidence found so far of an atmosphere on a rocky exoplanet. The discovery, made by a team of scientists from the University of Birmingham (UK), was made possible by observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), operated by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). For the authors, this discovery would explain the planet’s unusually low density, while challenging the established belief that relatively small planets so close to their stars cannot have atmospheres.

A planet less dense than Earth

With a radius 1.4 times that of Earth and an orbital period of less than 11 hours, TOI-561 b belongs to a rare class of objects known as ultra-short period exoplanets. Although its host star is only slightly smaller and cooler than the Sun, TOI-561 b orbits so close to it — 1.6 million kilometres — that the temperature on its day side far exceeds the melting point of rock. One explanation the team considered for the planet’s low density was that it could have a relatively small iron core and a mantle made of rock that is not as dense as the rock inside Earth.

On the trail of exoplanets

‘What really distinguishes this planet is its unusually low density. It is less dense than would be expected if it had a composition similar to Earth’s,’ notes lead author Johanna Teske of the Carnegie Science Earth and Planetary Sciences Laboratory. ‘TOI-561 b is different from ultra-short period planets because it orbits a very old, iron-poor star — twice as old as our sun — in a region of the Milky Way known as the thick disc. It must have formed in a chemical environment very different from that of the planets in our own solar system,’ suggests Teske. The planet’s composition may be representative of planets that formed when the universe was relatively young, the authors suggest.

A thick atmosphere

The team also suspected that TOI-561 b might be surrounded by a thick atmosphere that makes it appear larger than it really is. Although small planets that have spent billions of years baking in scorching stellar radiation are not expected to have atmospheres, some show signs that they are not just bare rock or lava. Using Webb’s NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) to measure the temperature of the planet’s day side, the researchers tested the hypothesis that TOI-561 b has an atmosphere. If TOI-561 b were a bare rock with no atmosphere to transport heat to the night side, its daytime temperature should be close to 2,700 °C, but NIRSpec observations show that it is closer to 1,800 °C, extremely hot but much cooler than expected.

To explain the results, the team considered several different scenarios. The magma ocean could circulate some heat, but without an atmosphere, the night side would be solid, which would limit the flow from the day side. Another possibility is that there is a thin layer of rock vapour on the surface of the magma ocean, but this alone would have a much smaller cooling effect than observed.

Although Webb’s observations provide compelling evidence that an atmosphere exists, the question remains open: how can a small planet exposed to such intense radiation retain any atmosphere, let alone one as substantial as this? “We believe there is a balance between the magma ocean and the atmosphere. As gases escape from the planet to feed the atmosphere, the magma ocean absorbs them back into the interior. This planet must be much, much richer in volatiles than Earth to explain the observations. It’s really like a wet lava ball,” explains Tim Lichtenberg, a researcher at the University of Groningen (Netherlands) and co-author of the study.